A missing half million?

Half a million dyslexic students may have missed out. According to the 2015 figures for England[1] the overall entry for GCSEs in summer 2015 was 4,916,000. Given the demography of dyslexia we could expect 10% of students benefitting from exam papers in accessible digital format, using inbuilt or third party assistive technologies to read questions accurately and respond effectively. This would imply some half a million papers accessed nationally in accessible digital format.

Doomsday scenario – but whose?

Half a million students using technology in their exams is a nightmare ‘doomsday scenario’ – the entire system would melt down. But there is no evidence that every student with dyslexic tendencies would request a paper in digital format. In Scotland, where accessible digital question papers have been available since 2008 the number of requests for digital papers in 2015 was a mere 3,562 – less than 4% of the total access arrangements requested. Some 44% of schools in Scotland requested digital papers serving an average of around eight candidates per centre. That is modest for centres to achieve but can be life changing for learners.

Consider the alternative doomsday scenario experienced by dyslexic learners on a daily basis. Your main support options are a reader or a scribe, neither of which supports your independence and autonomy as a learner. Readers and scribes are expensive provisions and so reserved for the most severely dyslexic students. Unless you are ‘lucky’ enough to be severely dyslexic you’re most likely to struggle daily with minimum support and be assessed in all your subjects through the one medium you find hardest to handle – text. Instead of providing freely available tools to help you work more accurately and effectively the one concession you get is more time (so you can spend longer working inaccurately and ineffectively).

The curtain of ignorance

Modest changes to teacher practice and IT infrastructure can transform the learner experience. The Equality Act is very clear that providing information in “accessible format” is a fundamental reasonable adjustment yet the average learning provider simply doesn’t do it for most students who need it. From inaccessible websites to inaccessible learning platforms, inaccessible curriculum resources and inaccessible examinations the average ‘print-impaired’ learner hits unnecessary barriers on a daily basis. Any court case could quickly establish the unreasonableness of the current situation but the single thing protecting most learning providers is ignorance. The students and their parents/carers are as ignorant of the service they could be experiencing as the learning provider is of the service they could provide. It would take a few tech-savvy students or parents to pull the curtain aside and reveal the inadequacy of provision. All our students will work in jobs that require 21st century skills and yet much disability support is indistinguishable from what might have been provided a hundred years ago – readers; scribes; one to one discussion.

Reasonable adjustment? I doubt it.

Working backwards to move forwards

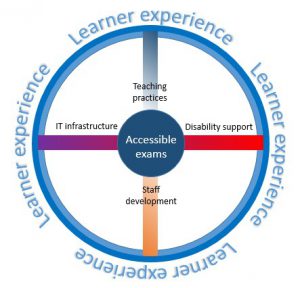

Ironically, one of the most effective ways of dealing with the curtain of ignorance may be to start at the end, not the beginning. By taking a strategic approach to access arrangements for exams organisations create the framework that improves accessibility practice throughout the learner experience. The image shows the interdependencies required to offer dyslexic and print impaired learners digital exam papers (click for larger version).

Ironically, one of the most effective ways of dealing with the curtain of ignorance may be to start at the end, not the beginning. By taking a strategic approach to access arrangements for exams organisations create the framework that improves accessibility practice throughout the learner experience. The image shows the interdependencies required to offer dyslexic and print impaired learners digital exam papers (click for larger version).

Unpicking the model

Most learning providers work on the basis of a ‘one-spoke wheel’ where the exam access arrangements are determined by the learner’s experience of a normal way of working. But the normal way of working is, at best, mediated by human intervention and at worst indistinguishable from any other student’s support. That is why the most common access arrangement is extra time. It is cheap and it reflects the day-to-day learner experience – take longer to do the work. But it does not reflect best practice.

The technologies available in the 21st-century should transform the day-to-day working of a dyslexic student. In an ideal world, they would be accessing books and handouts via a laptop, tablet or even their mobile phone. In some countries they already are. They could use inbuilt navigation features to rapidly scan the context of the information and use text-to-speech tools to speed comprehension and accuracy. They would plan responses using mindmapping or outlining tools and write up the details using word prediction or voice recognition. They would access presentations and handouts outside of the lesson using whatever learning platform was provided. They would be developing skills and using tools that would make them independent learners. They would be more confident, competent and employable.

Enabling the ‘normal way of working’

So how do we make this the normal way of working? Start by recognising that, for all their skills and experience, disability support teams are only a small part of the answer. The more inclusive the teaching resources and experiences are designed to be the more independent learners with additional needs can be. Wittingly or unwittingly the way teachers teach will either remove barriers for these students or create them. But good teaching has other dependencies. Technology may offer a range of benefits but you need to be trained in what is available, why it can make a difference and how to use it effectively. And training is only effective if the infrastructure is reliable and accessible. No one will waste time with systems that regularly crash or that require complex authentication with complex passwords that you have to change every month.

A touchstone?

I have read many inspection reports where providers get praise for models of support that seem to rely on intensive human interventions without tackling the unnecessary barriers created by the teaching resources. This is not a social model of disability. If Ofsted ever want a touchstone of good accessibility practice that provides a barometer of support for genuine independence I could suggest one.

“How many students are offered exams in digital format?”

If you can offer this to students there are a lot of other things your ‘normal way of working’ you must be getting right.

Welcome to the 21st century. Now all you need to do is make sure Ofqual ensures awarding bodies provide digital papers in accessible formats.

But that’s another story.

[1] Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2012 – https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-pupils-and-their-characteristics-january-2012